|

|

|

Canadian Breed History Part II

Part two

|

|

In 1865, the Board of Agriculture of Lower Canada offered a prize at the provincial exhibition for the best French-Canadian horse, and of the 22 entries, were disappointed to find that not one was of pure blood. In 1868 the Board considered forming a commission to search for stallions of the pure French-Canadian breed. (Photo L -Horse Fair, Sherbrooke, PQ Eastern Townships Research Centre)

|

|

But when local politicians representing them declared that there were no such horses to be found as they had all been taken to the United States, the Board regretfully concluded that the task would be almost impossible.

Had it not been for the tireless efforts of a small group of gentleman inspired by patriotism, the Canadian Horse may well have disappeared from our landscape forever. Dr. J.A. Couture, distinguished Quebec agronomist, Edouard Barnard, (who had worked so tirelessly for the preservation of the Canadien cow), and a few associates, remained dedicated to searching out, inspecting, and recording any remaining Canadian Horses of quality. Initial progress was slow – decades of depletion and crossbreeding had taken their toll, and the purpose of recording individuals not well understood by average horse-owners. Nevertheless, in 1886, the first registry for 'La Race Chevaline Canadienne' was opened, and Edouard's beloved stallion 'Lion of Canada' became #1 - the first registered Canadian Horse.

In the years that followed, over 1800 horses would be inscribed by hand in Volumes I and II of the first registry. Depending on the registrar, some entries were made with great care: with markings, birthdates, height, weight, pedigrees, changes of ownership dates, and progeny noted under the mares names. Some horses made the 2:30 mile requirement for Wallace's Trotting registry, and were double-registered, often under a different name.

(M. Joseph Deland, preeminent breeder, founder & president, French Canadian Horse Breeders Association 1909 - photo courtesy Société d'histoire de la Haute-Yamaska)

|

|

|

|

|

In 1895, the Canadian Horse Breeders Association ( La Société des Eleveurs de Chevaux Canadiens) was formed, took over registrations and proceeded to validate the integrity of the stud books entries and inspect the horses registered therein. With the passing of the federal Livestock Pedigree Act in 1905, all breed associations in Canada were encouraged to incorporate under one umbrella, to standardize registration procedures, and scrutinize their existing herd books to meet new federal regulations.

|

|

Each breed association had the choice of bringing their existing books up to standard, or starting fresh with new inspections to record their foundation stock. For the Canadian Horse, the task of bringing the old books up to standard would have been formidable - many horses had died, or could not be located as they been sold to other provinces or the United States, some without transfer of certificates.

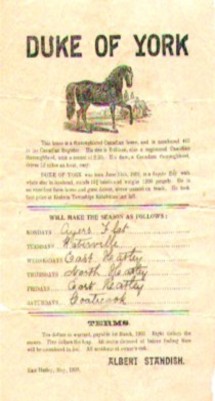

Dr Couture consulted with Dr. Rutherford, Canada’s first Veterinary Director General and Live Stock Commissioner, and they agreed that the best course of action would be to dissolve the existing registry, re-inspect registered horses, as well as previously unregistered horses of Canadian type for suitability as foundation stock, and cull any off-type horses from the breed record books. Dr. Rutherford informed the association of the procedures to be taken - only those horses that could pass inspection by a strict committee would be permitted entry into the new books. The new inspections continued until 1909, and out of 2,528 horses inspected, 969 were accepted as foundation stock. Many horses from the first books were not presented, but still well over 300 horses that had been previously registered passed the new inspections. Others were progeny of sires and dams registered in the old books. See Brillant (Duke of York, a chestnut stallion f. 1898, sired by Brillant, and owned by C.E. Standish, Ayer's Cliff, PQ is one of the horses registered in both books -ETRC)

|

|

|

|

|

Regrettably, the inspection teams did not inspect horses outside of Quebec and parts of Ontario, and those horses that had been sold to the United States or other provinces before the inspections took place, regardless of pedigree, were simply dropped from the registry, and lost to the breed forever.

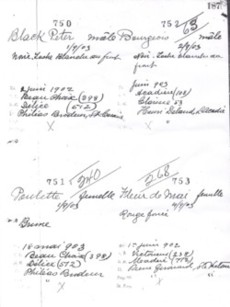

Dr. Couture still felt that the breed was in need of ongoing systematic preservation efforts. He lobbied for, and obtained support from the federal government, and in 1913, the government established a stud farm in Quebec at Cap Rouge, followed by a second at St. Joachim in 1919. Experimental breeding programs to conserve, revitalize and fix the type of the Canadian Horse breed were undertaken, but, as elsewhere, with mechanization, the use of horses diminished. The population of horses in Quebec dropped from one horse for every five inhabitants to one for less than every ten inhabitants over the next two decades.(Right - a copy of page 187 of the old Volume 1 of the geneaological record of 'La Race Chevaline Canadienne, showing the horses' new registration numbers in the new book above the old)

|

|

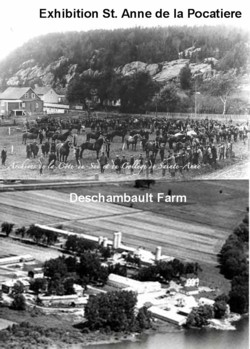

By the end of 1940, Canada was heavily involved in World War II. Motor vehicles had largely replaced the horse in agriculture, transportation and the military. The federal government withdrew financial support for the farms with the exception of a small operation at St. Anne de la Pocatiere. The Quebec Department of Agriculture purchased some stock and continued with a smaller breeding program at Deschambeault (La Gorgendiere) research farm. The rest were sold to private breeders who sometimes did not register their stock. (Photo R -Horses at Cap Rouge)

|

|

|

|

|

Once again, the alarm bell sounded for the fate of the Canadian Horse. In order to revive the breed, the association decided to temporarily re-open the stud-books in the early 1960s to mares that were of Canadian type, but had no recorded ancestry (see the Souche Mares). This second set of inspections continued throughout the critical period of the 1970s when breed numbers had dropped to less than 400, until 1984 when the stud books were again closed. Since then, all Canadian horses registered must come from two registered Canadian parents. Photo Archives de la Cote-du-Sud & Canadian Agricultural Library)

In November 1981, the remaining forty-four Canadian Horses at Deschambeault farm were sold at an auction reserved for members of the Canadian Horse Breeders Association, and the task of keeping the breed alive fell to private breeders. Thankfully, they held on to their horses, and continued to register them. By the end of the 1980s, breed numbers began to slowly increase.

|

|

In 1994, an Ontario CHBA member began to lobby his MP to have the Canadian Horse recognized and honoured as the National Horse of Canada. Over the next few years, the movement grew and gained support. Meanwhile in 1999, the Canadian Horse was made an official heritage animal of Quebec.

Canadian horse owners and admirers from across the country, still wanted national recognition and united in lobbying their members of parliament for their endorsement of the proposal. After several tries, a bill put forth by MP Murray Calder, and Senator Lowell Murray, was passed by parliament and received Royal Assent (becoming law) on April 23, 2002

Finally, the Canadian Horse had received official recognition as the National Horse of Canada.

|

|

|

|

|

Although still endangered, thanks to the efforts of dedicated breeders, owners and admirers, the Canadian Horse is making a remarkable recovery, and now claims almost 5000 registered individuals. In spite of dwindling to only a few hundred in the 1970s, a genetic study conducted by researchers at the University of Guelph, Ontario in 2000, shows that the breed still maintains better genetic health than some other breeds with higher numbers, and is free from any known genetic defects.

Today’s ideal Canadian Horse, still closely resembles the spirited horse captured by Faillon’s pen over 150 years ago. A Canadian Horse typically stands 14 to 16 hands high, weighs 1000 to 1300 pounds, and is generally black in color with few, if any, white markings. Bays, chestnut, and occasionally rare champagne colors are found within the breed. The ideal Canadian has a finely chiseled head, strong arched neck, a long sloping shoulder, short back with well-muscled hindquarters, strong, flat-boned legs and exceptionally hard, strong hooves. The distinctive hallmark of the breed is its long, thick wavy mane and tail. The mane is often so thick that it falls on both sides of the neck and hangs below its shoulder, its tail so long that it touches the ground. Canadian Horses are confident, intelligent, hard-working, and sociable, and still have all the endurance and adaptability of their ancestors. In 1990, two purebred Canadian Horses, a nine year old mare, and a three year old gelding, spent eight weeks in the sub-zero temperatures of the Arctic when they accompanied the POLARLYS Expedition to Cornwallis Island.

|

|

The Canadian Horse is excelling in all disciplines as horsemen and women across rediscover its timeless qualities of style, durability, intelligence and loyalty. Canadians consistently excel in Combined Driving Events and can be found successfully competing at the international level. They can also be found in all under-saddle disciplines - from reining, cutting, and endurance riding, to dressage and jumping. The Canadian Horse’s powerful hindquarters and athletic ability make it an ideal candidate for ranch work or collected movements. The national Canadian Horse Breeders Association (CHBA) boasts almost one thousand members, nine- tenths of those living in Canada.

In order to be registered All Canadian Horses must have their DNA on file for parentage testing. In addition foals must be identified by microchip or tattoo. Artificial insemination by either cooled or frozen semen is permitted, as is embryo transplant. This enables even small breeders to have a good selection of prospective stallions to breed to, and helps ensure that the rarest bloodlines within the breed will survive and be available to breeders across great distances.

|

|

|

|

|