|

|

|

BREED ORIGINS

|

''Version française, cliquez ici''

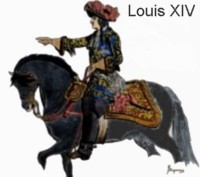

The story of the Canadian Horse begins in 1665, when the French sun king, Louis XIV sent the first horses to New France to be distributed among the military officers of the Carignan-Salieres regiment, government officials, and religious communities of the colony. The first fourteen royal horses destined for the New World left Le Havre on the ship Le Marie Therese on May 10, 1665. After nine perilous and stormy weeks at sea, two stallions and twelve mares set hoof on the shores of New France at Tadoussac on July 16th. Another shipment of 15 royal horses arrived on September 25, 1667, with similar shipments reported in 1668, and 1669 (Thomas Chapais 1914). In 1670, a stallion and twelve more mares arrived to be distributed among the gentlemen of New France. A final shipment of thirteen horses arrived in 1671, for a total of eighty-one horses.

|

|

|

|

|

While no one yet knows with certainty the lineage of these royal stallions and mares, we do know that France has a history of breeding distinguished horses dating back to antiquity. Several hundred years before Christ, horses were used in Gaul for military purposes and in 58 B.C., Julius Caesar noted the elegant, well-bred horses of the region in his diary. Small Asturian horses (Asturcones) from the Pyrenees mountains that were highly prized in their mountainous home territory for sure-footedness became popular as carriage ponies in Paris and throughout Europe, and many were were exported to the British Isles where they contributed to founding the Galloway and Fell ponies. The now lost medieval 'destrier', the Norman Horse, when crossed with the oriental blood of the Arabian and Barb, contributed to the later development of the Percheron ánd Spanish-Norman breeds, renowned for their excellence on the battlefield.

|

|

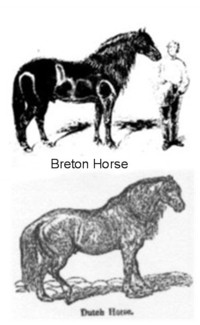

In northern France, stock was heavily influenced by the stock of the "Low Countries". The English army requisitioned over 10,000 horses from the Netherlands in the 1500s for the invasion of France. Dutch horses were valued for their ability to outwork the English horses three to one. In the 17th century, strong Flemish horses were brought to Poitou to drain the marshes. Cotentin and Breton horses were prized for their smooth, brisk gaits and their ability to survive under harsh conditions. Even today, there is a marked similarity between Canadian Horses and the ancient Asturcone, Corlay Breton, Friesian, Merens, and Murgese breeds.

|

|

|

|

|

Louis was known for his lavish tastes and loved to surround himself with baroque and beautiful things. His horses were no exception. He imported Iberian stallions to cross with hardy French mares to produce elegant, durable mounts for his Maison Royale, for the cavalry, and for the equestrian arts. Horsemanship and horse-breeding flourished during his reign with the founding of the equestrian school of Versailles and the Haras Nationaux (1665). When completed, king Louis XIV's Gran Ecurie at the Palace of Versailles housed over 600 royal horses.

|

|

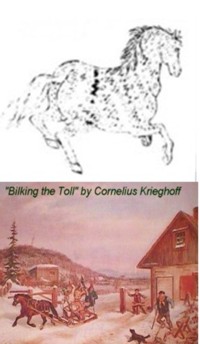

Records and artwork from the past survive to help us imagine what the king’s horses looked like. New World Jesuit missionary, Louis Nicholas, saw one of the first stallions to arrive in New France and while his sketch in the Codex Canadiensis is crude, he recorded in his diary that the stallion was one of the most beautiful he had ever seen. A century later, Dutch-Canadian artist, Cornelius Krieghoff painted the descendants of the kings’ horses on his canvas, and French historian, Etienne Faillon, captured the essence of the breed with his pen: " small but robust, hocks of steel, thick mane floating in the wind, bright and lively eyes, pricking sensitive ears at the least noise, going along day or night with the same courage, wide awake beneath its harness, spirited, good, gentle, affectionate, following his road with finest instinct to come surely to his own stable."

A century later, western artist, Frederick Remington, would write in "Horses of the Plains"(1889) that "the French Canadian pony, and the Morgan, for all practical purposes, are the best horses ever developed in America."

|

|

|

|

|

Northern French territory in those early times included not only Quebec, but what is now Vermont, New York, Michigan and Illinois. French horses found their way to the southern outposts, to French settlements at Chimney Point and Crown Point on the shores of Lake Champlain, and to the Jesuit mission farms near Detroit and on the shores of the Illinois River.

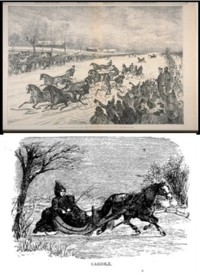

The horses adapted to their new frontier environment better than any other domestic animal sent to New France and soon became indispensable to the habitant: hauling wood, bringing in the harvest and maple sugar, working in the grinding mills, and providing much needed transportation over the ice of frozen rivers during the long cold winter months. It was near Montreal, in sleigh races across the ice, that the North American sport of harnessing racing began.

|

|

Canadian Horses saw early military service too. In 1759, they were used by the “Corps de Cavalrie” until the surrender of Montreal in 1760. General Montclam himself rode a fiery black stallion into battle on the Plains of Abraham.

In 1777, 1500 Canadian Horses were purchased by The British army from Montreal and surrounding areas and used on General "Gentleman Johnny" Burgoyne's ill-fated southward march to Ticonderoga. Canadian Horses served with the “Volunteer Corps” through the War of 1812, and the Militia Cavalry during the Fenian troubles. During the worst years of the Patriote Rebellion, 1837 and 1838, the British army and volunteer militias are reported to have stolen over 800 Canadian Horses when they burned, pillaged, and destroyed French Canadian villages in Lower Canada.

|

|

|

|

|

The Canadian breed became renowned for its abilities as a roadster, racer and stylish harness horse. By 1820, classes for Canadian Horses were being held at agricultural exhibitions in Lower Canada and in New York. Over the next decades, increasing numbers of Canadian horses, including the best stallions, were sold to the United States. Many found their way into the foundation stock of other breeds such as the Morgan, Tennessee Walker, American Saddlebred and Standardbred.

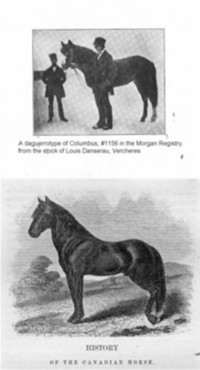

Even today, as evidenced by a genetic similarity study conducted by the University of Guelph, Ontario, in the year 2000, the Canadian Horse and the Morgan are still close genetic cousins. Two of the most famous Canadian stallions to leave Canada were Old Pilot (1829), and St. Lawrence ( pictured left -1846). Other Canadian Horses were exported to England where their easy-going nature made them popular as London omnibus horses.

(Top Left - stallion Columbus, owned by the Danserau family, Vercheres, PQ. Sold to the U.S and became #1156 in the MHR (Morgan).

|

|

With the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War in 1861, Canadian Horses once again were used for miltary service when thousands were exported to supply the Union Army. By the end of the war in 1865, at least 30,000 Canadian Horses had been exported for military service. Following the Civil War, and the horrendous loss of human and equine life, American buyers continued to come to Canada for horses. Old Québec newspapers such as "Courrier de St. Hyacinthe" reported on the influx of American buyers and the trainloads of Canadian Horses shipped south.

Later, in 1874, Canadian Horses took part in the historic North West Mounted Police Great March West, in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 and are even said to have served in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Canadian Horses sent to serve in the Boer War in South Africa did so well that hundreds were subsequently purchased for the British Imperial forces and shipped overseas. During World War I, more Canadian Horses were shipped off to battle in France, never to return.

|

|

|

|

|

Ironically, the popularity and availability of the Canadian Horse almost caused its demise as a distinct breed. Breeders began to realize the impact of losing their best stock, but even though all agreed that the Canadian Horse was in urgent need of conservation and replenishing, there were long and heated debates on how best to accomplish this task. One side felt that the Canadian horse was perfectly adapted to the Canadian climate and way of life, so it would be best to seek out any remaining native stock and rebuild the breed from those horses.

The other side felt that the breed had been so eroded by cross-breeding and export that there were not enough remaining individuals of quality as in previous generations. They reasoned that it would be better to resuscitate the breed by importing horses of similar ancestry, such as the Percheron from France, to cross with Canadian stock. The latter viewpoint found much favour with some influential academic agriculturists and politicians such as Louis Beaubien, director of the Quebec-based Haras National and importer of Norman, Percheron and Arabian Horses.

NEXT

|

|

|